Long before he turned himself into a symbol, Prince was already playing with the curvy shapes of numbers and letters, writing lyrics dangling with figures and signs. Where EE Cummings cast language as a kind of sensual child′s play – soft little letters cosying up to one another – Prince’s view of the seductive power of words was much more adult: an “erotic city” jumping with vibrant colours and capitals. At the centre of his world was the question of U: what was this entity, what force did it have compared with a garden-variety “you”? Whether adored, damned or worth dying for, “U” had the look and pull of a magnet – an irresistible hook.

With Prince, letters and numbers have an ultra-concentrated power, holding a firm place in his personal cosmology. In this spirit, he rechristened almost every member of his tribe. Glamorous women had the status of minor deities in his universe: Vanity 6 gave way to Apollonia 6 and even an Electra, while his reliable stalwarts (Sonny T, Michael B, Sheila E) hung by a single initial, like chords ready to strike, always on time.

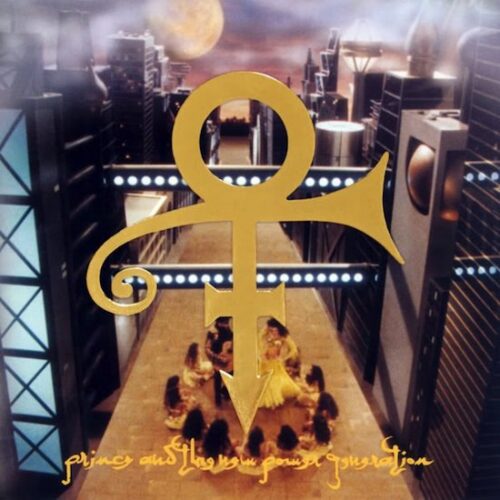

We can hear numbers ringing and chiming throughout 1992’s Love Symbol, from the top-to-bottom excitement of ‘Love 2 The 9’s’ to the leggy ‘Sexy MF’ to the majestic ‘7’, in which the title is wielded like a gold sceptre, bringing down nations and humbling enemies. At the end of ‘Love 2 The 9’’, the maximalist imagery of love boils down to a binary code ("2 the 9s, 2 the 9s"), which is where the real frisson seems to occur: at the level of sex between symbols.

Magic figures rule the narrative that underscores this album. The entire record is wrapped up in a Technicolor fantasy of Arabia, starring Prince as a heroic insurgent, fighting seven assassins while fixing his eye on the ultimate prize, the king’s daughter. We are dealing with established tropes: the prince who was a thief, the romantically pursued couple, the daredevil with the comic touch of a Fairbanks; all that’s missing is a flying carpet.

In 3 Chains O’ Gold, the film Prince directed to accompany the album, we see the full extent of this delirium, as the artist plays a rather foppish Prince of Persia to Mayte Garcia’s belly-dancing princess, alongside pastiches of the Arabian Nights and plenty of nudity. Could anyone else have pulled off this softcore fantasia? Unlike so many lauded artists, Prince did not require an epic basis for his songwriting – the inspiration for a glorious track was as likely to be some half-remembered kitsch from 50s Hollywood as a classical reference. Under The Cherry Moon (1986) showed us that the greatest songs might be underpinned by the cheesiest of plots: a novelette, a soapy melodrama, anything to unleash the imaginative splendour of the music. The story Prince chose to soundtrack could be stale or original: at any rate, it provided an excuse for rhythm and invention.

More than any other 20th century musician, Prince represents the artist as magician, as merry-maker: the one whose mastery of craft allows him to remain light-hearted, dashing off songs on the slimmest pretexts. There is a feeling of exhilaration and speed in his work – as opposed to labour – and a key element of wit, which undercuts his frequent allusions to divinity. During this phase of the early 90s, we can see his work in all stages of development, from the small sketch (‘Eye Wanna Melt With U’, and from the following year, ‘Peach’) to the long-form piece that represents a summary of his career to date (‘My Name Is Prince’).

In ‘My Name Is Prince’, the artist frankly presents himself as the seventh wonder of the world, and here is the evidence to back it up. The opening is a storm of aggressive beats and warning cries; within the blitz, snippets of ‘Controversy’ (1981) and ‘I Wanna Be Your Lover’ (1979) can be heard as proof of his past glories. Both are unusual choices, since the former is a confession of self-doubt, while the second is about vulnerable yearning ("I wanna be the only one that makes U come, running!" is pronounced with such a genuine, eager bounce that it cuts through obvious innuendo). But the frontal attack of ‘My Name Is Prince’ contains many different moods: having flaunted his might and revealed himself as God’s ultimate creation, Prince goes on to claim: "I ain’t sayin’ I’m better, no better than U." He takes the moral high road, invoking the Lord and "a better way", yet he is unable to deny himself the fantasy of seizing the young princess. With his signature mix of boasting and humility, Prince was the king of contradiction ("I got two sides and they both friends"). The compulsive flow of this track means that he can voice all kinds of opinions without conflict: there is no separation between the macho bluster, the gallant rescuer and the voice that yelps "Hurt me!" As the inclusion of ‘I Wanna Be Your Lover’ shows, there are pockets of tenderness within this headlong assault.

Why was Prince able to get away with so many dualities, disdaining riches while anointing himself as the gold standard? The loving fingering of jewels in 3 Chains O’ Gold has a fetishism that recalls Kenneth Anger, but the singer decries "fancy clothes" and trophy women while coveting the princess. One of the reasons Prince remains mysterious is that he could be of several minds simultaneously – for instance, when performing ‘I Could Never Take The Place Of Your Man’ live, he would often interrupt the song with camp asides ("He don’t look like me", "His hair is not like mine") without losing its central emotion. Each time he would return to the sober phrasing as if refreshed by the joke, his intensity unabated by these flashes of humour. He might begin a song by praising purity and condemning decadence – or vice versa – only to get the two categories confused. In 3 Chains O’ Gold, the Egyptian princess Mayte represents the former, her sheltered upbringing adding to her mystique. However, when the two meet, it is Prince who appears veiled and elusive to the awed princess, his face covered by chains. His style of seduction is mercurial, alternating chivalry and mystery with obscene suggestions, as with ‘Sexy MF’, where he discusses erections and the life of the mind in the same breath.

For Prince, most boundaries were blurred: he could not conceive of freedom as anything other than sexualised. With all the talk of intersectionality in the last decade, it is startling to come across an artist who simply equated sexual denial with cultural and racial oppression. Staying independent meant being lascivious, as much as tattooing the word "slave" on one’s face with an ascendant "V". Liberty, intelligence, creativity – these were principles of eros, so interrupting the status quo involved a necessary defiling of the body ("I put my foot in the ass of Jim Crow"), as in ‘My Name Is Prince’. But even here there was room for impish good humour: in the midst of his tirade, Prince cries, "When U hear my music, you’ll be havin’ fun / That’s when I gotcha, that’s when U mine!" This song is the kind of surrealist dream in which a major threat consists of being subjected to fun – a musical subjection, since Prince leaves most of the violent taunts to rapper Tony M.

‘My Name is Prince’ ends with two male voices trying to work out what a woman just did ("She came!" "Where?" "There!"). With that ringing in our ears, the next track, ‘Sexy MF’, is presented as the "there", the coming, even though it is tantalisingly slow in getting to the point. While Prince launches straight into seduction mode, he begins with a sly feint of keeping things purely cerebral ("It’s U I wanna do / No, not cha body your mind U fool"). According to the first verse, this song is about the "R.E.A.L. meaning of love", and if a woman assumed otherwise, that was her own dirty mind at work. Prince was fond of pulling these counter-intuitive moves, acting affronted at having his virtue questioned. At the inference that his motives might be less than pure, he would come back with shocked retorts of the "get your mind out of the gutter, Missy" variety, before getting down to lewder and lewder requests.

It was a one-two provocation that never failed to thrill: Prince playing the fainting violet, then revealing that it is he who controls the game all along. In ‘Sexy MF’, this kind of about-face (which matches the song’s turnaround hook) involves telling a girl "this ain’t about the body" while not losing sight of her dimensions ("a long, leggy 5 foot 8 / Packing an ass as tight as a grape"), and even offering a blindfold as proof that "this ain’t about sex". It seemed that Prince could keep an equally keen eye on women’s measurements and their souls, dangling a luxe package of travel and education ("I just want U smarter than I’ll ever be") and proposing to cook and clean for his future wife! At which point, one might ask: what kind of sex jam talks so much about housework, hugs and marriage?

Ever the contrarian, Prince saw romance and devotion as punk – in a society in which graphic sex was a given, marriage was the consummate turn-on. As a man who delighted in creating new erogenous zones – his costumes basically re-mapped the male body, so that its soft, luscious parts might seem sexy – it was natural to seek a further set of taboos. Monogamy began to seem like the ultimate aphrodisiac, if only as a concept, so that the focus on snuggling and companionship was not entirely disingenuous. To each woman he would describe a lush, exotic pleasure dome, like the inside of a genie’s bottle, firing the imagination in a way which is the essence of erotica. Yet this sensitive courtship was punctuated by the most leering of "yeahs", promising that matters could only stay G-rated for so long.

Musically, ‘Sexy MF’ takes us to the brink every time: horn stabs create the expectation of a climax, only to return us to the holding pattern of drums and rhythm guitar, a percolation that keeps our nerves on edge. There is no harmonic progression. Prince biographer Jason Draper has criticised the single as a "riff in search of a song", but perhaps it is really a test of how long that search can be prolonged. For Prince, who could so easily resolve a song to satisfaction, ‘Sexy MF’ is all tease; as he notes towards the midpoint: "U seem perplexed I haven’t taken U yet." But the track is less about "taking" than fooling us with a series of false endings, so fulfilment is always put off. This occurs the second time the horns deliver their ultimatum, bringing us to a precipice – but instead of a huge leap, there’s a sudden soft landing: Prince gives a tame pecking kiss, not even a smooch, and it’s a backing vocalist who sings, "U sexy motherfucker". Even by the end of the track, desire remains delayed, its restraint a powerful move in a world of excess.

It was often Prince’s style to offer too much and then pull right back – to lay on all the bells and whistles (or one of his amazing repository of squeals) before giving us stripped-down rock and jazz, music that shows its bones. In his body of work, richly embroidered fantasies sit alongside the simple sparseness of ‘Peach’ (1993) and ‘Cream’ (1991). There is a tension between clean beauty and showy glamour in his songs, which tend to present him as a gigolo with good intentions (toting the "pimprag, tootsie pop and a cane" of ‘Arrogance’). As such, Prince is a kind of Scarlet Pimpernel figure: the noble hero who disguises himself as the most useless of lounge lizards, claiming to show more interest in décor than action.

As a child, I always assumed that Prince was the nighttime avatar of the Count from Sesame Street: after all, both were purple and math-obsessed, and got up to God-knows-what-kind-of decadence in their palatial homes. Like Prince, the Count was a mannered yet convincing aristocrat, dedicated to the study of colour and number, and intent on imposing that pattern of perfection on the world. Later on, Prince’s ‘7’ seemed to be the adult version of the Count’s theme tune ‘8 is Great’, in which a beloved number is invested with dramatic powers.

In ‘7’, Prince’s multi-tracked vocals come together like pillars, upholding a vision of "streets of gold" after the fall of a regime. It is a song of praise, carried by stately Middle Eastern themes, but this anthem is also a death warrant: here, Prince’s fixation on counting is an unabashed glee in seeing his opponents crushed. The serene intonation of the chorus is deceiving; we hear drawn-out assertions that "we’ll love through all space and time, so don’t cry", but tears are quickly resolved with a curt statement: "One day all 7 will die." The seven assassins are not merely token obstacles to love; there will be a genuine joy in watching them suffer, literally one by one. The singer counts out the feet of the enemy army as they march to the slaughter: “words of compassion, words of peace” can’t silence the desire to “smoke them all” and see blood spilled. Along with the seven assassins, six traitors will be killed, and the song relishes their deaths by counting them. Although the second last line of each stanza suggests tolerance, we always close on an image of death (“watch them fall”).

That Prince could write a song of such magisterial calm driven by schadenfreude shows up the contradictions inherent in his talent: the ability to create elevated work from what others might regard as petty grievances, to transform hokey sentiments into singular imagery. For Prince, the chronically musical performer – he could hardly turn out a phrase that was unmemorable – it was often a matter of felicity as to what he might fuse together. On this album, he laced a hard-edged assault with humility, mixed flashy and elemental imagery ("like Evian and the deep blue sea"), and reserved his sleaziest lines for a sophisticated jazz number.

The story of Love Symbol allowed him to play out all of his ideal roles, even if they occasionally came into opposition: avenger, trickster, peacemaker, lover, aesthete. What other performer evokes such a range of fictional archetypes, from Des Esseintes, the collector of exotic sensations, to the Wizard of Oz, whose gaze simply filtered out colours which failed to harmonise? Like the Scarlet Pimpernel – another dandy known by a single symbol – Prince reconciled spiritual devotion with the glamorous life, presenting himself as a soulful libertine. Along with the pleasures of the harem, he wanted to experience repose, commitment, conjugal bliss – nothing less than the whole world at once.